For the past three years, the dominant investment thesis, shared by venture capitalists and Sovereign Wealth Funds (SWFs) alike, was predicated on the scarcity of compute, particularly around the high-performance GPU clusters used to train foundation models. This led hyperscalers like Amazon, Microsoft, Meta, and Google, to collectively spend over $300 billion annually to secure Nvidia GPUs and build data centers (which Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang calls “AI factories”). While some of this expenditure is rooted in expected model training requirements and trends in end-user adoption rates, it also reflects a defensive response to the risk that a competitor gains a dominant platform position in the AI markets.

The scramble for capacity has led to full orderbooks and high margins for Nvidia GPUs, Broadcom networking chips and GE Vernova gas turbine generators used in the data centers. In the three years since Dec 1, 2022 (the day after Open AI released ChatGPT), Nvidia’s stock price has increased 12x, and Broadcom’s 7x. GE Vernova stock has increased 4x since its IPO in April 2024. Open AI is not traded publicly but its value is estimated to have increased 17x during the same period. Hardware and foundation models have captured a disproportionate share of industry value in this period. Who will own the value in the next phase of industry growth?

While investment in infrastructure to support training larger models in the quest for artificial general intelligence will continue, the overall AI compute workload is shifting from model training, which is a capital expenditure, to inference, which provides economic benefit or entertainment to end users, who presumably at some point need to pay enough for these services to support all the capital investment. Currently the key revenue streams are primarily end user subscriptions, usage fees paid by enterprise software accessing AI models through programming interfaces, and enhanced advertising revenue driven by AI for players like Meta and Google.

Growth of the market will be dependent on continuing to expand the application of inferencing in services that deliver value to end users. While chatbots will expand their audience, agentic processes, where an AI service is able to plan, reason, and act around a goal, are expected to drive the largest growth. This could be around optimizing a factory process, or it could be planning the kid’s playdates. Visual transformers, diffusion models, and vision-language-action models (which control robots) will become more important as “Physical AI” begins to serve the 80% of the global workforce that is on the front line rather than behind a desk.

Changing Economics

The economics of delivering AI services will play a key role in how broadly these services are adopted.

Nvidia continues to improve the cost/performance of its chips, but late 2025 has brought changes suggesting some erosion of the “hardware moat” that has enabled Nvidia to gain more than $4 trillion in value. The release of DeepSeek V3.2 and Google’s Gemini 3 challenges the assumption that model performance is linearly correlated with massive, expensive compute. DeepSeek V3.2, which matches GPT-5 performance, was trained for a fraction of the cost of its Western counterparts. Algorithmic breakthroughs like Sparse Attention have reduced the cost of training, and this will continue. Simultaneously, custom silicon chips such as Google’s Trillium TPUs, which was used to train Gemini 3, and Trainium 3 chips from AWS are substituting for Nvidia GPUs for many workloads at a fraction of the cost. The spot price for rentals of Nvidia’s workhorse H100 GPU, which peaked at over $8.00 per hour, has fallen to as low at $1.60 per hour at the end of 2025.

Tokens are the measure of AI workloads, both for words and data ingested after a prompt, and the resulting output. Tokens for the advanced AI models may cost $15-$60 or more per million. So, there is a real economic cost for a query. A simple Chatbot query may require a few hundred tokens, while a complex reasoning or agentic request may require a hundred thousand or more. Consumers have become accustomed to “free” internet service, paid for by accepting advertising, or perhaps paying a nominal subscription fee for something like streaming video. If advanced AI services are priced at $10 or more per task, they will be limited to higher value enterprise or professional applications. When they come down to pennies per task, they will be used ubiquitously. Hence, many high-volume end-use markets are likely to be quite price sensitive, putting pressure on “AI factories” to reduce the cost per token.

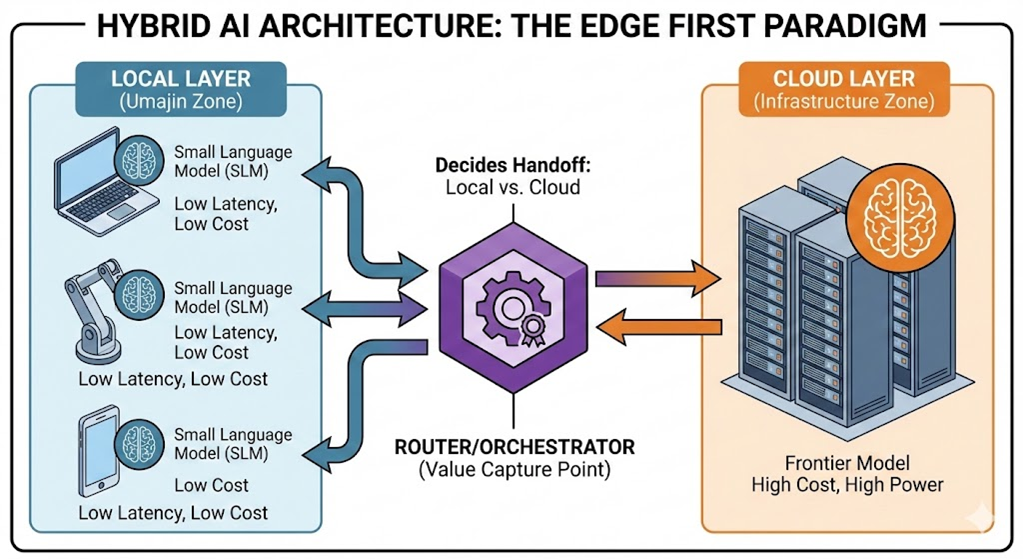

Several factors are going to drive deflation in token pricing. The stock market is starting to show concern about capital investment getting ahead of revenue, this will most impact debt financed build out by players like Oracle and Coreweave, but is likely to put margin pressure on both data center operators and suppliers. Better algorithmic efficiency of large language models as has been demonstrated by DeepSeek 3.2 and Microsoft’s BitNet, which can reduce cost for certain types of workloads. We expect to see more migration to small language models for many inferencing tasks, many of which can be run on lower cost edge devices. Physical AI applications, which often put a premium on low latency since they may be controlling physical processes, will also accelerate edge migration. New hardware including Neural Processing Units and ASICs optimized for inferencing for edge devices will play a role. And hybrid application architectures will help orchestrate cost reduction by processing much of their workload on lower cost edge hardware, and send only complex inquiries to expensive cloud GPU clusters.

Value Capture in the Downstream Market

The growth of reasoning models, agentic applications, and physical AI enabled by continually improving models, lower token process, and application that embed AI in the users’ workflow will create real economic value. What factors will drive how much of that value is retained by upstream hardware and “AI factory” providers, versus application vendors?

In previous tech cycles, hardware price erosion resulted in much of the profit pool being captured by software. In the AI buildout cycle (2022–2025), hardware has been the primary bottleneck and value captor. The capital expenditure required to train and host frontier models continues to rise, meaning that a small group hardware, AI companies, and hyperscale data center operators will control the “intelligence utility” for frontier models, so long as models continue to advance. They will not see significant value outflow, although competing open source and smaller custom AI models will grow in importance.

AI enabled downstream business models will see value inflow, but it will not be evenly distributed. The price of inference (using the model in applications) is dropping. Lower cost generative AI lowers the barrier to writing code, making it easier to build applications. This creates a flood of “wrapper” apps, increasing competition and destroying pricing power downstream for these “thin” applications. If an application’s primary value is “using AI to do X,” and AI is accessible to everyone, the application has no competitive moat.

The “moats” of the future will be:

- Intellectual Property: Patents that anticipate technical convergence.

- Proprietary Data: Typically, non-public customer data sources that enable truly differentiated capabilities.

- Agile Development: The ability to rapidly deploy new business models using a platform optimized for integrating and orchestrating AI tools and enterprise data within a defined governance framework

- Customer Relationships: Established through deploying high-value solutions.

Demand will be divided among many verticals markets. The “The AI Market,” will become “The AI-Driven Logistics Market,” “The AI-Driven Grid Market,” etc. This favors the “Integrators” and “Platform” companies, that control the IP for the emerging applications. The defining characteristic of this architecture is the “System-of-Systems” approach. In this paradigm, an AI model is not a standalone product. It is a component within a larger system. Consider a Logistics Hub. The ‘wrapper’ app just writes an email about a delay. The ‘System-of-Systems’ uses vision AI to detect the delay, updates the ERP, re-routes the truck via IoT, and notifies the driver—all without human intervention. This complexity is where the value lies. It is far harder to replicate this integrated workflow than it is to replicate a text-generation model.

The AI bubble is not likely to collapse, but it will slowly deflate. The “AI Factory” market may see a shakeout, especially among debt financed operators. Hardware providers will remain profitable with reduced margins. “Thin application” companies (including some legacy enterprise software providers) will struggle. The developers of industry-focused “systems-of-systems” that have sufficient IP to have freedom to operate and to create a competitive moat will capture a large share of the value generated by AI growth.